It’s not everyday that you meet a kindred spirit, someone you feel an instant relatability to or connection with, but I met one on Sunday. Correction: I met her proxy.

Our sugarhouse restaurant was busy last Sunday morning. Many families came in for breakfast, and lots of new visitors came in the front door and lingered, looking hesitant, like we might make them flip their own pancakes. But a unique young gentleman stood out from the crowd: he walked in the front door and came straight over to the maple counter with a purpose. He must have been twelve years-old.

“Hi,” he said, before glancing at a slip of white paper in his hand. “Can I please get a half gallon of medium or dark syrup?”

Good manners, I thought. “Sure,” I said. “Do you have a preference, or either one works?”

He paused and thought. “I don’t know,” he said. “My mom made me come in here. She gave me this list, and it says medium or dark.” He held up the list and gave me a look that said help a brother out.

“Got it,” I said. “Let’s give you dark because it’s really good, it’s what we serve in the restaurant, and we have a lot of it this year.”

After I rung up his order, he paid and thanked me, and I nodded out the window as I watched him go. Godspeed, Mother of that Kid, I thought. You and I are one. I commend you. Go forth and prosper.

I am an only child, and getting sent in places by myself like that was a through line of my childhood. I remember one afternoon, I was sitting in the car with my mom’s best friend Shelley.

“You know what sounds really good?” Shelley asked.

“What?” I said.

Shelley pointed at a nearby movie theater attached to the mall. “Movie theater popcorn.” She made a hard turn and pulled the car parallel in front of the entrance to the theater. Car still running, she handed me some money and said, “Alissa, run in there and buy us some popcorn!”

I hesitated. “But don’t you have to see a movie to get movie theater popcorn?”

“Nah,” she said. “Now get on in there. It’ll be fine!”

I grabbed the money and climbed out of the car. I looked behind me to see her smiling face from the front seat. I walked in the entrance and, it being the middle of a weekday, the lobby was practically empty. The ticket attendant cleaned the rug with one of those tiny, silent vacuums and watched me enter.

“Hi,” I said. “I uh, just want to buy some popcorn. Can I do that?”

He paused and looked confused. Had he ever encountered this question before? It didn’t seem like it.

“Ummmmm, okaaaaaay,” he said, stretching out his words. “I guess you can.” He turned and pointed at the concession stand.

When I came back outside with her snack, Shelley picked me up, and I handed over the bag of yellow, buttery popcorn.

“Oh!” said Shelley. “This is SO GOOD!”

I remember my mom telling me to call my doctor’s office so I could practice making an appointment on my own. I do not remember her checking on whether or not I did my homework. Of course I did my homework, why wouldn’t I? I did my homework, I walked myself to and from school with my friends, and I even put Tide liquid laundry detergent on my friend Terry’s brand new white collared shirt when he was hanging out in my yard and spilled Hi-C on it.

“It didn’t even stain,” he told me the next day. “That soap you put on my shirt, it worked.”

Cut to: present day, and I have three kids of my own. Note: three kids, not one. Another note: three boys, not three girls. Somehow, amidst the chaos of having these three boys, I am only now poking my head above ground to discover that I didn’t have time to teach each of them how to be capable and independent. It’s still early, they are young, but they have grown up a bit, and now we speak a different language. At their ages, I was checking the classified ads, looking for my own apartment.

“Grab that bag by the door and that water bottle and bring it out to the car, please,” I said to one of my sons, I won’t say which.

“That bag?” he asked. “The blue one? The one with the handles? By the front door?”

“Yes, that one,” I said.

“And bring it to the car? Right now? Is it unlocked?”

“Oh my God,” I said. “Yes! That bag with the handles! Get going!”

People in my mom’s generation would say I’m a softie. People in my generation would say I’m a hardass.

“Alissa, I need you to be bad cop,” said my friend Eli at my middle son’s first official baseball practice. I laughed.

“I love that I am the designated bad cop,” I said. “I’m tired of that job. Baseball season is going to be my vacation. Why don’t you have Chip do it?” I pointed to my husband.

“Chip and I are too…” he trailed off.

“Too what?” I said.

“We’re too nice,” he said.

“Chip? Ha-ha. Good one!” I said. Some are better at hiding it than others, I thought.

“Bring your dishes in, please,” I said to the boys after dinner.

Only one boy out of three brought his dishes to the counter.

“Now put them in the dishwasher.”

[A HUGE SIGH.] “I don’t even know where they go.”

“I’ll show you.” Again, I think as I walked over and showed him. [ANOTHER HUGE SIGH.] He sulked out of the kitchen and to his room.

This is pitiful, I thought. My mind flashed back my days working at the local co-op. My co-worker Nate worked in prepared foods, and one afternoon I walked by to see him wiping down his station. He had washed the knives and put them away, labeled the containers, and meticulously wiped the counter back and forth so as not to miss a spot.

“Nate,” I said. “You keep your workspace so clean. This is incredible. You must be the world’s best roommate.”

“It’s thanks to my mom,” he said. “She taught me to do this starting when I was young.”

I was pregnant with my first son at the time, and I distinctly remember thinking, I’m going to be like Nate’s mom.

“Bring your plate into the kitchen, please,” I said to my youngest.

“Nope!” he said, hopping up and turning his back to walk away.

“Grab your plate,” I said, dropping the please bullshit. “And bring it into the kitchen.”

“I don’t think so!” he said, laughing. He seemed to think he was cute.

“Get. In. There. And. Bring. Your…” I’ll let you imagine where this went.

“I swore at one of the boys,” an auntie told me one afternoon at the sugarhouse. “He wouldn’t bring his plate in, and it just slipped out. They probably think I’m a mean auntie!”

“No, they don’t. And it’s fine. Thank you! I mean it. They need to hear this stuff from people other than us,” I told her. “They have had terrible behavior at the sugarhouse and pretty much everywhere else,” I said. “We are going to take care of it.”

“How can I make my kids listen to me?” I asked my counselor Stephen. I recently got back in touch with him, asking for a fresh appointment after a decade. I read articles about how remodeling is one of the most stressful things/first world problems a family can go through, and I like to be prepared. But thanks to Aunt Wendy letting us live in her empty house, Stephen and I have been able to turn to everyday topics.

“Scratch that,” I said. “I don’t want them to listen to me. I want them to do what I say. I’m looking for total submission.” He laughed. Why is he laughing?

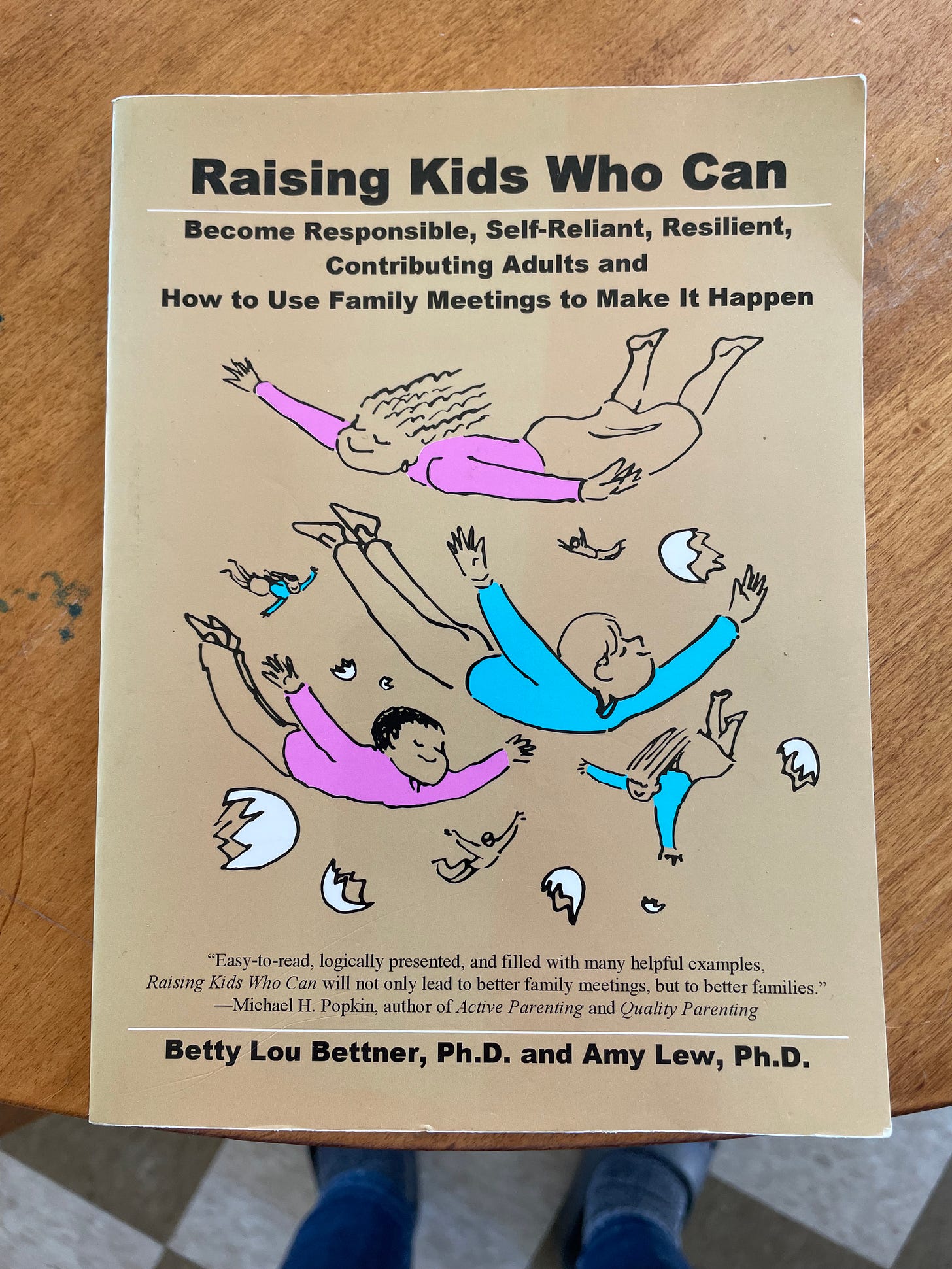

“I have a book that might help,” he said, getting out of his armchair and walking to his bookshelf. “It’s about the family meeting. I think this could give you some good results.”

“A family meeting?” I said, flipping the book over in my hands. “I’m guessing this is an alternative to screaming in the mirror?”

Good student that I always will be, I read the book in two days, took notes, and scheduled our first family meeting for the next Sunday evening. I nominated myself to lead the first meeting as it was my (Stephen’s) idea, clearly ignoring the part of the book that said, “Parents, don’t rush in or talk too much.”

Once the five of us were seated in Aunt Wendy’s kitchen around her wooden miniature of King Arthur’s Round Table, I said, “Welcome to the first Williams family meeting.” Someone groaned. “Hey!” I snapped. “Don’t blow this before we get started.”

“First, we will start with appreciations,” I said, hating the words coming out of my own mouth. Appreciations? Come on. Mom and Shelley would roll their eyes at this hoo ha.

The concept of appreciations in ‘Raising Kids Who Can’ says that starting on a positive note sets the tone for the meeting and reminds everyone that each family member contributes to the whole. The book states, in more gentle terms, that if these younger people see themselves as growing, capable humans instead of drooling children that can’t bring a damn plate in, they feel more confident and stop acting like ding-dongs.

“I’ll start,” I said. “I appreciated when you,” I said, turning to our youngest, “divvied out my vitamins into the little holder thing. I hate doing that, and thanks to you, I took my vitamins.” I remembered his chubby little hands dolling out one by one and felt a rush of warmth toward him. Then I remembered how he dumped the entire bottle on my bed afterward and refused to pick them up.

“Who wants to go next? Chip?” I said, giving him eyes that read Go next and help me, or else.

“Ok,” he said. “I appreciated all four of you helping out at the sugarhouse this weekend.” We all nodded and smiled. Lovely.

“Next?” I said.

“I’ll go,” said my middle son. “I appreciated when you,” he said, turning to his older brother, “didn’t crap your pants when you farted this morning.” They burst out laughing. Chip and I looked at each other with pursed smiles before remembering that jokes were no longer funny. They would never be funny again.

“Guys, listen up,” I said. “Hey!” I waited until they all looked at me.

“We have a problem, a family problem.” They all fell silent, finally. “You are all good kids, each of you, and we love you,” I said. “We are starting like this because your behavior is not great lately. Not great at all. I am afraid we are becoming a mouthy family. A mouthy family that can’t do basic things.”

“What does mouthy mean?” asked our six year-old. I turned to him.

“It’s a way of speaking to people that is rude and not helpful. It’s disrespectful. I’ll show you. Tell me to please bring my plate to the kitchen.”

He looked uncertain. “Go ahead,” I said.

He whispered, “Please bring your plate to the kitchen.”

I looked him in the eye. “Nope,” I said in my best imitation of a mean girl. “You can bring the dishes in yourself.” His eyes widened. “That,” I said, looking around, “is mouthy.”

The table was silent. I looked at Chip, and he nodded in agreement.

Boy, my own mouthiness sure was convincing, I thought.

I turned to our middle son, the nine year-old. “Do you remember in the dining hall when I asked you to bring my glasses up to the dish area?” I said. What is it with these kids and dishes? He nodded. “We were with our friends, and you literally said, to your mother, ‘I’m not bringing up your dishes.’”

He opened his mouth in protest but smartened up and closed it. He nodded again, likely recalling how he went nuclear after I pulled him aside. Then I went nuclear like a mean girl on steroids. It was grim, and he lost video games for a week.

“It’s not about caring what other people think, it’s about how we treat people. This behavior is terrible at home, and now it’s spilling out into the world. We’ve had it.”

While on the one hand, I sufficiently killed any buzz of warmth and democracy in our first family meeting, on the other hand, I did cut to the chase. Why mince words? This first meeting was a fire alarm, a call for life support, not a time to share hugs and come up with a family cheer. We could do that later after everyone stopped acting like total buttholes.

“Look, we can do this!” I said, invoking the pronoun ‘we’ out of the goodness of my heart and switching from Mean Girl to Cheerleader.

“You’re good kids, let’s start acting like it,” said Chip.

“Are you with us?” I asked.

“I’m with you,” said our eleven year-old, my official favorite son of the day. "I won’t be mouthy. I’ll be respectful.”

“Me too,” said our middle son.

Chip and I both looked at our youngest. He laughed and then tried to chew on his smile to hide it.

“How about you?” I said.

He laughed again. “May-be,” he said.

I gave him faux mean girl eyes. “Okay,” he said.

A few days later, I was walking down Main Street in my town when I saw this poster hanging outside the local karate studio:

It reads: “As a son respects parents, younger brother respects older brother. Man must always respect his elders and seniors. This is the beauty of mankind and one of the distinctions between human and animal.”

There never was a clearer message. The universe was responding to my plight. But OUCH, human and animal? Perhaps the sign was a tad severe, comparing us to animals (primates), but I knew what the owner, Karate Instructor Master Nam, was going for. Maybe we need to get the boys into karate, I thought. I also thought to harp on this sign for only using ‘son,’ ‘brother,’ and ‘man,’ until it occurred to me that us women are such glorious creatures that we’d never even need such a sign.

After a week of improved behavior from our boys, I forgot I was a glorious creature and turned into my own version of pitiful.

“Do you think your mom is mean?” I asked my sons in a ridiculous plea for reassurance.

This is our latest cycle: Chip and I use democracy and respect to try to live with the boys in peace. No one listens to a damn word we say, and peace turns into hell. Chip and I lay down the law. The boys work on things and start to act sweet again, and then I feel bad for the times I yelled, forgetting that they were total monsters. (Only I feel bad. Chip feels fine.) Repeat.

“You aren’t as mean as you think,” my mom tells me, and I appreciate that. I know I have got to stop this cycle of feeling bad. But I don’t like yelling, and I wanted to break the cycle of my father and grandfathers. And yet, I also understand. Time and time again, we only reach the points of progress after… you guessed it! We yell. When we go for democracy, these boys treat us like a joke. The youngest literally laughs in our faces. And mama ain’t standing for that.

I am also a recovering Catholic. The main lesson I absorbed is that no matter what, at the end of the day, it is all my fault. I never thought I’d be like this, and I thought I was getting better, but the guilt really stuck. Or did I hear that I’m innately guilty because I’m a woman once on TV? Good thing I worked out all of these religious and societal issues before I had children.

“Mom, you’re not mean,” said my middle son. “I promise!”

“I just want you guys to learn to…”

“Poop?” said my youngest.

“We know,” said the nine year-old. “You want us to learn how to do things because we’re getting older.”

“Exactly,” I said.

“Dang it,” said the six year-old. “I guess I was wrong.”

A few days later, I opened my birthday letter from my eleven year-old. It read:

“Dear Mom,

First of all, I want you to know you are a good mom and not mean or crazy at all! I also hope you have fun…”

The letter went on to say funny and sweet things, but I paused and looked up at the sky. That’s cute that he put ‘at all’ in bold letters, but I don’t think I ever used the word ‘crazy.’

“Can we have another family meeting tonight?” asked our youngest.

“Wow, you want another one?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “And another one tomorrow.”

I guess Stephen’s book was successful after all, I thought. My youngest was still a chocolate-covered mess, but he was only six. We’re talking about someone who picks the skin off his feet and eats it.

Later that night, I tucked him into bed.

“Kissy?” he asked. I leaned over him. “Give me those juicy lips," he said.

I laughed and gave him a kiss… or what I thought would be a kiss. Instead of a smushy peck on the lips, he pressed his lips to mine with force, held the back of my head, and poked his little tongue into my mouth. There was something on the very tip of his tongue, something slender and pokey.

I brought my hand to my mouth, retrieved a tiny half moon from my tongue, and said, “Did you just pass me a fingernail?”

He burst into maniacal laughter.

This is the beauty of mankind… one of the distinctions between man and animal.

Perhaps we will find that distinction when he’s seven.

Thanks for reading.

XO

Alissa